Translated by E. Annamalai and H. Schiffman

1.

Whether town or forest

whether lowland or hill,

In whatever way people are good

the earth is good.

Long may it prosper.

(Auvaiyar, Puranaanuuru 187)

2.

Too late, jasmine . . .

Young heroes won’t wear you,

bangled women won’t gather you,

bards won’t bend your branches low

with the crooks of their graceful harps,

to pluck you. You blossomed after Satthan of the strong spear

died, he who, valorous to the last,

conquered many warriors,

did in his many enemies.

Alas, too late for the Ollaiyuur country, jasmine.

(Kudavaayil Kiirattanaar, Puranaanuuru 242)

3.

A shield, you say, a shield?

Yes, a shield and a stone to stave off the enemy,

and you may survive.

The brother of the one you slew yesterday

is searching for you, his eyes jumping

like the crab’s eye seed, rolling around

on a white plate.

is search is like that of a thirsty man

for a glass of wine

in an empty house.

(Arisil Kilaar, Puranaanuuru 300)

4.

In the courtyard

where munyai and susundai

are spread to dry,

its shade so vast, sleepers

need no roof, the elephant hunter rests.

A lone stag frolics with its mate,

she who is doomed as bait for future hunts.

Willing neither to disturb this happy union,

nor to rouse her husband,

the mistress of the house sits quietly.

Even the partridge and the wood- fowl

in stealthy nibbles, gobble up the millet,

now drying on a deer hide.

There you shall stay awhile, my bard;

partake, with your dark kinsmen,

of generous slabs of meat and aaral fish,

roasted on a sandalwood fire.

It is a house well known

for never failing to shelter

reward seekers,

favored by the king.

(Viirai Veliyanaar, Puranaanuuru 320)

5.

She said:

We used to build sand castles,

and he used to wreck them.

We!d put fresh blossoms in our hair

and he1 d snatch them out

and even steal our balls of yarn.

This rascal, oh my bright-bangled friend,

who troubled us in all these ways

came (without my realizing it was he)

to our house.

My mother and I were alone.

He asked for water-

My mother filled a golden cup

and I took it to the door,

still unaware of who it was.

When I offered him the cup,

he clutched instead my bangled wrist.

I shouted, "Mother! Look what he’s doing!"

My mother rushed to me,

but I could not betray him.

I said he had hiccoughed.

While my mother rubbed his back,

he eyed me with a killing look,

and smiled.

(Kabilar, Kalittokai 51, Kurinji)

6.

She said:

There are good omens: the house- lizard chirps,

and my dark-rimmed left eyelid flickers.

My lover is gone,

but I know he will come (yes, I know–

money must be earned, ascetics must be fed,

but most of all, I know that

we will live our life in love) .

Listen to what he said.

He said the heath was so hot,

you could not tread it

but he said the he- elephant

saves the last puddle of water,

though sullied by its young,

for its mate.

He said the sight would pain the eyes–

leafless trees, dry branches,

and no mark of pleasantness.

But there the he- dove would fan

with its soft wings, to console its

tired young loving mate.

He said the hot sun would scorch

all the bamboos on the hills,

affording no protection for those who would cross.

He also said the stag would give

its own shade, there being no other,

for his suffering mate.

Virtuous, from the trial of this forest,

he will not allow my beauty to fade;

I am certain he will come soon.

(Paalai paadiya Perungadungo, Kalittokai 11, Paalai)

7.

Her friend said:

When my friend gave you neem- fruit,

green and unripe,

you likened it to sweet, soft candy.

Now, even if her gift

is just water in the winter-month of Thai,

from the cool rivulet on Paari hill,

you find it hot and bitter, my lord.

Such is the nature of love.

(Milaikkandan, Kuruntokai 96, Marudam)

8.

She said:

There were no witnesses

when he embraced me.

(If he leaves me now, what can I do?)

Only a heron stood by,

its thin gold legs like millet stalks,

eyeing the aaral-fish,

in the flowing water.

(Kabilar, Kuruntokai 25, Kurinji)

9.

She said:

Crescent-winged bird flies swift

after the setting sun

in a wide sky.

Fresh prey, and hungry young mouths

to pop it in

in the tall tree

near the cave.

(Taamoodaran, Kuruntokai 92, Neydal)

10.

Her mother said:

Disdaining even sweet white milk and honey,

she heeded not the bidding of nursemaids (gold pot

in one hand, raised stick with flower- soft tip in the other)

but tottered on her baby feet

to the garden;

gold pearl-filled anklet jingling.

A spoiled child.

Whence cometh now the wisdom and new

ken of kitchen? Her husband’s fare

is meager, yet she does scorn

and send back food her father offers, untouched;

turns at fasting leave her,

like the white-black bands on the river1 s bank,

faint

and yet strong.

(Poodanar, Narrinai 110, Paalai)

11.

Her friend said:

Eyes askance,

hands cupped to mouth,

the women (in small groups and not so small)

are tattling on us. My friend,

fresh flowers from the grove

could not be sweeter

than the honey- colored mane

of that steed, drawing the chariot,

which my lord rides.

Shall I leave with him at midnight?

Then to hell with these townsfolk and their gossip!

(Ulooccanaar, Narrinai 149, Neydal)

12.

He said:

My heart says, "Go to her, unbind the thongs

of suffering from her soul."

She of the cool- lidded eyes,

whose outlines are dark kuvalai blossoms,

and long black tresses hanging low.

My mind: "A job undone will bring disgrace;

rush not."

My body bears the tension of these two–

a worn-out rope pulled from both ends

by elephants

with bright upswinging shiny tusks.

(Teeypuripalangayirranaar, Narrinai 284, Paalai)

(Note: The name of the poet, Sangam anthology’s name & verse number in the anthology are given after each poem above)

Sangam Poetry

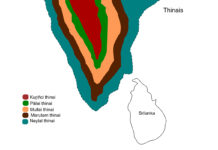

The above poems come from the various anthologies of Classical Tamil poetry that belong to the Sangam (Cankam) age, circa 200 B.C. to 200 A.D. Sangam means an academy, though there is no evidence that the various poets in fact formed an academy, or for that matter any other organized group. Sangam poetry falls into two main categories: Akam, “interior” or love poetry, and Puram, “exterior” or heroic poetry. Puram poetry is represented here by the selections from the Puranaanuuru, while the remaining selections are of the Akam from the other anthologies, Kalittokai, Kuruntokai, and Narrlnai. In the anthologies of Akam poetry, the poems are arranged according to their setting (landscape, time of the year, fauna and flora) which also prefer certain themes:

1.Kurinji: hilly landscape; pre-marital meeting of the lovers.

2.Neydal: seashore; heroine’s anxiousness about the hero’s indifference.

3.Mullai: pastoral landscape; patient waiting by the wife for the husband away on duty. 4.Murudam: river bank; bickering arising out of the hero’s infidelity.

5.Paalai: arid land; pains of parting between husband and wife or the mother and the eloping daughter.

Most of the poems are in the form of monologues, and the characters in the love-drama appear as speakers: Hero (He); Heroine (She); Her Friend; Her Mother; etc.

Acknowledgement

The above translations appeared in Mahfil, Vol. 4, No. 3/4, TAMIL ISSUE (Spring and Summer, 1968), pp. 13-20. Published by: Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University.