By Govindaswamy Rajagopal

Present-day man has become absolute mechanical and obsessed with material gratification. Up till the period of industrialization, evidently he lived ‘the natural life’. Despite facing serious threats all the while, perhaps danger every minute, yet the erstwhile man’s life was in nature and the nature was in his life. His ‘interior feelings’ and ‘exterior actions’ were indeed ostensibly governed by the natural environment wherein we find a variety of insects, amphibians, crustaceans, reptiles, mammals, birds and animals1. The creatures of soft and wild nature were brought into relationship with mankind by the poets of Sangam Age (c. 300 B.C.–A.D.250) to convey the nuances of human feelings of love such as excitement, ecstasy, anxiety, separation, sulking, solitude, sorrow, etc. Living beings are portrayed in Sangam poems not as isolated elements but as their integral parts to reveal “the interior landscape” so aesthetically. An abundance of descriptions, similes, metaphors, ‘implied metaphors’ or ‘insets’ (uḷḷuṟaiuvamams), and ‘hidden meanings’ (iṟaiccis) that involve ‘the interior feelings’ and ‘the exterior actions’ of birds and animals are extensively employed as symbols/codes in akam (= love) poems of Tamil Sangam Literature to express deeper meaning of the subtle love feelings of humankind viz. puṇardal (sexual union), iruttal (patient waiting), ūḍal (sulking), iraṅgal (anxious waiting) and piridal (separation). Often, ‘akam poems tend to hinge around one or more images, exploiting the complex suggestion of images to the full’ (Hart 1979: 3).However, the present paper can deal only with a selection of themes with regard to the main akam landscapes and more details may be discussed on a latter occasion as the genre deserves it.

Birds and Beasts Found in Five Landscapes:

Classical Tamil love poetry artistically portrays human love experiences in specific habitats loaded with natural background. Every situation in the poems is described using themes in which the time, the place and the floral symbols of each episode are codified. These codifications are used as symbols to imply a socio-economic order, occupations and behaviour patterns, which, in turn, are symbolized, by specific flora and fauna.

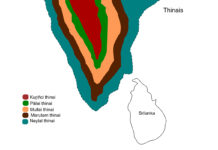

Love in Sangam poems was dealt with in five tiṇais, viz. kuṟiñci, mullai, marudam, neydal and pālai– the five landscapes (regions) that are named after plants in the tract of land that they grow in. Each tiṇai pertains to a particular region with its own suitable season and appropriate hour of the day and its flora and fauna and characteristic environment. The aspect of love is called the ‘uripporuḷ’, i.e. ‘the subject matter of the tiṇai’; ‘the region, the season and the hour’ are called the ‘mudal poruḷ’, i.e. ‘the basic material’; ‘objects in the environment’ are denoted as ‘karupporuḷ’.

Kuṟiñci-tiṇai, the clandestine union of the lovers is characteristic of the mountainous region; mullai-tiṇai, the life at home spent in expectation of the return of the hero is set against the background of the forest region; marudam-tiṇai, the sulky life has agricultural region as its background; neydal-tiṇai, the life of despair is characteristic of the sea coast; pālai-tiṇai, the life of desolation in separation is depicted in arid landscape. Besides these five tiṇais, there are two non-geographical modes which also deal with human emotions viz. ‘kaikkiḷai’ and ‘peruntiṇai’. Since the love themes of these two tiṇais were unnatural, they were not associated with any specific landscape. Kaikkiḷai deals with ‘unreciprocated’ or ‘one-sided love’ whereas peruntiṇai deals with ‘improper love’ or ‘love against the rules of custom’.

Kuṟiñci – Mountainous Region:

Kuṟiñci, the tiṇai representing a mountain region, speculates on the ‘Union of Lovers’ at midnight. It is originally the name of the famous flower Strobilantheskunthiana growing in the mountain region. The Strobilanthes (a shrub whose brilliant white or blue flowers blossom for only a few days once in every twelve years) is symbolic in indicating the blossom of the feminine senses ready to become united with the male physically and spiritually.

Vaṇḍu (beetle), curumbu (honey bee), ñimiṟu (honey bee), tumbi (denoting both honey bee and dragon fly), kiḷi (parrot), maññai/mayil (denoting both peahen and peacock), pāmbu (snake), kuraṅgu (monkey), mandi (female monkey), kaḍuvaṉ (male monkey), paṉṟi (wild pigs), varaiyāḍu (mountain goat/sheep), āmāṉ (wild bull), eṉgu (bear), yāṉai (elephant), puli (tiger) etc., are the birds and beasts of the kuṟiñci region which is filled with bamboos, jack fruit and vēṅgai trees. The occupants of mountain region are tribal people who hunt and gather honey. The place is cool with water in abundance and represents the midnight hour of a day.

The poems of kuṟiñci-tiṇai describe the clandestine love affair of young girls. A heroine in Kuṟuntogai (KṞT) anthology, who is so happy about her bosom relationship with a young man, delightfully declares:

nilattiṉumperidēvāṉiṉumuyarndaṉṟu

nīriṉumāraḷaviṉṟēcāral

karuṅkōṟkuṟiñcippūkkoṇḍu

peruntēṉiḻaikkumnāḍaṉoḍunaṭpē. (Poet: Dēvakulattār, KṞT. 3)

Bigger than earth, certainly,

higher than the sky,

more unfathomable than the waters

is this love for this man

of the mountain slopes

where bees make rich honey

from the flowers of the kuṟiñci

that has such black stalks. (Tr. A.K. Ramanujan, 1985: 5)

The kuṟiñci poem cited above does not describe the lovers’ union explicitly but does so implicitly. As observed by A.K. Ramanujan (1985: 244), “the union is not described or talked about; it is enacted by the “inset” scene of the bees making honey from the flowers of the kuṟiñci”. The implied meaning is that the mountain owned by her man was the most preferred location for young men to have sex with their sweethearts. Here kuṟiñci flowers in connotation signify young girls; honey bees young men; and making of rich honey by the insects denotes young men and women indulging in merrymaking sexual acts. It may be noted here that often women especially teenage girls are denoted as flowers whereas men, especially teenage boys, are symbolized by honeybees. In the poem, her lover is not only the lord of the mountain; he is like the mountain he owns. This technique of using the scene to describe an act or agent in Tamil is known by the grammatical term ‘uḷḷuṟai uvamam’, ‘hidden’ or ‘implicit metaphor’.

As rightly observed by George L. Hart III (1979: 6):

The Tamils were and are an agricultural people, and for them fertility is the most important aspect of human existence. In kuṟiñci, the most important human relation – that between man and woman with its promise of offspring – has been initiated, but has not yet been controlled and ordered by marriage.

Thus, the secret union of the kuṟiñci poem is pervaded by a sense of imminent danger – if the hero delays marrying his beloved for some reason or other. In the majority of the kuṟiñci poems, the dangerous aspect of secret love (i.e. gossiping about the modesty/chastity of heroine) is more realistically described mostly by tōḻi (sakhi in Sanskrit, the companion or female friend of the heroine) and some-times by the heroine herself. In Kuṟuntogai 38, the heroine describes in anguished tones her lover’s callousness/insensitive attitude of delaying the marriage with her.

kāṉamaññaiaṟaiyīṉmuṭṭai

veyilāḍumucuviṉkuruḷaiuruṭṭum

kuṉṟanāḍaṉkēṇmaieṉṟum

naṉṟumaṉvāḻi tōḻi uṇkaṇ

nīroḍorāṅguttaṇappa

uḷḷādagaṟalvalluvōrkke. (Kabilar, KṞT. 38)

He is from those mountains

where the little black-faced monkey,

playing in the sun,

rolls the wild peacock’s eggs

on the rocks.

Yes, his love is always good

as you say, my friend,

but only for those strong enough

to bear it.

who will not cry their eyes out

or think anything of it

when he leaves. (Tr. A.K. Ramanujan, 1985: 25)

The poem reveals the mental agony of the heroine (who is yet to be married to her lover) to her friend. Evidently, she is not pessimistic about the intentions behind her lover’s attitude. But by describing the aforesaid analogy about his mountain region, the heroine apparently reveals the insensitive attitude of the lover on the wedding issue. She suggestively refers the hero to the black-faced male monkey and herself to an egg laid by a peahen on the rocks. The hero from the mountain region (kuṟiñci) somehow develops and manages an inti-mate relationship with a girl of his region. The monkey symbolizing the hero keeps playing with the egg of peahen (i.e. the heroine) for days in bright sun-light and wishes to continue without showing any concern for the egg, i.e. the heroine. Without really thinking about it, he delays the marriage. Thereby he gives room for others to gossip about their relationship. It becomes a problem to what extent her position appears to be ignominious. So the heroine ponders over his attitude. Though his love is loyal, he lacks sensitivity. Sometimes, he is not seen for days. Thereby, it becomes the serious matter of worry for the heroine who is charged emotionally over him. “I survive since I am strong enough and hopeful”, so says the heroine.

Monkeys usually mishandle anything; play mischievously with the things that they acquired and disfigure them by their merrymaking mood. “Like a garland in the hands of a monkey”, thus a proverb in Tamil chronicles about the insensitive attitude of the monkey. Here in the poem, the ‘not-so-handsome man’ from a mountain region some-how manages to secure a bosom relationship with the beautiful girl of his region. Peacocks (maññai/mayil)2 are known for their ever attractive, quite charming and delightful beauty. When a monkey manages to obtain an egg of peahen, needless to say, it cannot handle it with care. Nevertheless, the monkey enjoys it at any cost by playing with the egg. It cannot realize the danger involved with the egg when it plays. The monkey is a wild animal and insensitive whereas the egg is a so-delicate/so-sophisticated substance carrying the soul/life force to be born sooner or later. When the shell of the egg (read here the physical body of the heroine) is in danger of being mishandled, the same could be expected to happen to the life force (chastity) of the heroine sooner or later.

Mullai – Forest/Pasture Landscape:

Mullai, the tiṇai representing the forest region, speculates about the patient waiting of a wife for her husband at evening time. It is the name of the specific flower of the forest region ‘jasmine’ (Jasminumauriculatum). The flower, growing abundantly on forest cum pasture land, symbolically represents the married woman. Its white colour and exceptional fragrance signify “the pure” and “blissful” life of married women. No doubt, mullai is a theme wholly concerned with fertility. The ideal family life led by man and woman duly holds out promise for their offspring in due course.

Cēval (wild fowl), maññai (denoting both forest peahen/pea-cock), ā (cow), āḍu (goat/sheep), kaṉṟu (calf), māṉ (deer), iralai (male deer), muyal (rabbit) etc., are the birds and beasts of the mullai region which is filled with rich lakes, waterfalls, teak, bamboo, sandalwood trees. In this region millet grows abundantly and wild bees are a source of honey.

Often, mullai poems give vent to the worry of a wife who patiently waits for the arrival of her husband. Occasionally, the poems do sketch the kind-hearted heroes who return to their homes after completing a mission successfully. In a mullai poem, a hero who is much charged emotionally over his wife is returning through a forest/ pasture landscape. Though he is very eager to reach his home at the earliest opportunity to make himself and his beloved wife happy, on his way back he advises his charioteer to slow down the chariot. Why did he say so? Let us see the following Akanānūṟu(ANU) poem:

vāṉamvāyppakkaviṉikkāṉam

kamañcūlmāmaḻaikārpayanduiṟutteṉa;

maṇimaruḷpūvaiaṇimalariḍaiyiḍaic

cempuṟamūdāypaṟattaliṉnaṉpala

mullai vīkaḻaltāayvallōṉ

ceygaiyaṉṉacennilappuṟaviṉ

vāappāṇivayaṅgutoḻiṟkalimāt

tāattāḷiṇaimellaoduṅga,

iḍimaranduēmadivaḷava! kuvimugai

vāḻaivāṉpūūḻuṟubuudirnda

oḻikulaiyaṉṉatirimaruppuēṟṟoḍu

kaṇaikkālampiṇaikkāmarpuṇarnilai

kaḍumāṉtērolikēṭpiṉ

naḍunāḷkūṭṭamāgalumuṇḍē (CīttalaiCāttaṉār, ANU. 134)

Rains in season,

Forests grow beautiful.

Black pregnant clouds

bring flower and blue-gem

flower on the bilberry tree

the red-backed moths multiply,

and fallen jasmines

cover the ground.

It looks like

a skilled man’s work of art,

this jasmine country.

Friend, drive softly here.

Put aside the whip for now.

Slow down

these leaping pairs of legs,

these majestic horses

galloping in style

as if to music.

Think of the stag, his twisted antlers

like banana stems

after the clustering bud

and the one big blossom

have dropped,

think of the lovely bamboo-legged doe

ready in desire:

if they hear the clatter

of horse and chariot,

how can they mate

at their usual dead of night? (Tr. A.K. Ramanujan, 1985: 76–77)

Mullai, being the region adjoining the fertile cultivable land, becomes bedecked in the rainy season with a variety of flowers which are full of fragrance. During the season, bees and birds used to throng over mullai region as people assemble at a place where a carnival is taking place. When bullocks pulling carts or horses pulling chariots return to their respective sheds after carrying out their day’s work in the evening, they obviously speed up their run without whips. Here in the poem the hero is the signifier signified by horses. And his emotionally charged mind is signified by the galloping speed of horses. As we know, as such horses usually symbolise the man of strength who is also sexually active and strong. A hero instructing the charioteer to slow down the speed of galloping horses implicitly meant that he was making his emotionally charged mind quiet for some time. His sentimental empathy with the stag and the doe will obviously delay his home-coming and thereby will prolong the suffering of his wife at home. But it is a noble feature of the ideal family life where everyone is supposed to have sympathy for all living beings. That is how in the poem, ‘Nature’ is brought into relationship with man, furnishing lessons and analogies to human conduct and human aspirations.

Quite evidently, the mood of mullai is one of fertility, mirrored by the greening of the woodland meadows in the monsoon after the summer. Some poems celebrate the union between man and woman (Aiṅkuṟunūṟu411); others describe the despair of the heroine, separated from her lover when all that surrounds her reminds her of that union. In Kuṟuntogai 190, the heroine shares her anguish/despondency with her tōḻi in the absence of the hero who assured her that he will soon return from his journey:

neṟiyiruṅkaduppoḍuperuntōḷnīvic

ceṟivaḷainegiḻacceyporuṭkagaṉṟōr

aṟivarkolvāḻi tōḻi poṟivari

veñciṉaaraviṉpaintalaitumiya

uravurumuraṟumaraiyiruḷnaḍunāḷ

nallēṟiyaṅgutōṟiyambum

pallāṉtoḻuvattorumaṇikkuralē (Bhūdampulavaṉār, KṞT.190)

May you live long, my friend!

Will he who stroked my thick,

black hair and wide shoulders,

and caused my stacked bangles

to slip off

as he departed to earn wealth,

hear

the tinkling of a single bell

whenever a fine bull,

in a stable with many cows, moves

in the middle of the night

when thunder rumbles, cutting

off the green heads of snakes. (Tr. Vaidehi)3

The hero, without marrying his beloved, has set off to a foreign country to gain wealth. He has promised to return by the monsoon, a time when travelling is difficult. The monsoon has arrived but not the husband, as he assured his beloved he would. The wife, who could not see him in person and missing him emotionally too, remembered the blissful days that she had earlier with him. As she is dried up passionately and unable to sleep during the nights of the monsoon period, the wife wonders whether her husband is aware of the arrival of the rainy season here in her place. She expresses her grief of loneliness to her friend, which may be paraphrased in the following manner:

Is my husband aware of the prevailing rainy season here wherein I am suffering? In the middle of the nights of the rainy season when thunder is often pealing, a fine bull, stabled with many cows at our shed, moves here and there. Thereby the single bell tied to its neck tinkles incessantly. Also the snakes have lost their tendered heads on hearing the rumbling sound of the thunder. So I am shaken and sleepless for nights.

The heroine simultaneously elucidates the two different attitude of her husband. Before setting off to a foreign country, more often than not, the husband stroked her thick black hair and wide shoulders passionately. Thereby, he gave her opportunity many times to experience the blissful part of the conjugal life. In his absence due to the state of loneliness, the wife became dejected, thin and pale, causing even the bangles to slip off from her arms. She suggestively expresses that she is not in a position to withstand anymore the rainy season that arrived with roaring thunder which troubles her to a great extent psychologically and sensually. In a way, the frightened bull and snake seem to be symbolically referring to the heroine who is also equally frightened by the roaring sound of thunder. So she seeks the broad shoulders of her husband to feel the sense of safety as well as to have the sensual enjoyment of his solace.

Marudam – Cultivable Landscape:

Marudam, the tiṇai representing agricultural pasture landscape, speculates on verbal and mental conflicts that take place between wife and husband (due to the infidelity of the latter towards the former) at early morning hours before sunrise. It is named after the tree “Black winged myrobalan”/“Terminaliaarjuna” (Lagerstroemia speciosa). It is a fertile, watery countryside. The hero of crop landscape enjoying life in abundance with plentiful resources often maintains extramarital relationship with younger and beautiful woman. Marudam poems often portray the scene of triangular love plots in which the hero’s visits to the concubine/harlot/whore oblige the heroine to counter with a mixed show of coquetry and sulking.

Mīṉ (fresh water fish), āmai (tortoise), nīrnāy (otter), kuruvi (sparrow), kōḻi (hen), cēval (cock/fowl), kokku (heron), kārāṉ, erumai (both the terms mean buffalo), mudalai (crocodile), kaḷavaṉ (crab) etc., are the birds and beasts of the marudam tract which is filled with ponds brimming with water, and plantain, sugarcane plants and tress such as marudam, mango, and neem.

Often, in the love poems of marudam-tiṇai, ‘Nature’ is used in allegories called ‘uḷḷuṟaiuvamam’ or ‘the implied simile’. All the objects of ‘Nature’ and their activities stand for the hero, the heroine and others and their activities in the drama of love. The latter are not at all mentioned but only suggested through the former. It is ‘simile incognito’ which leaves it to the reader to discover it. For instance, let us see a wonderful sketching of marudam-tiṇai poem from Akanā-nūṟu.

cēṟṟunilaimuṉaiyiyaceṅkaṭkārāṉ

ūrmaḍikaṅgulilnōṉtaḷaiparindu

kūrmuḷvēlikōṭṭiṉnīkki

nīrmudirpaḻanattumīṉuḍaṉiriya

antūmbuvaḷḷaimayakkittāmarai

vaṇḍūdupaṉimalar arum ūra!

yāraiyōniṟpulakkēm, vāruṟṟu,

uṟaiyiṟandu, oḷirumtāḻirumkūndal,

piṟarum, oruttiyainammaṉaittandu,

vaduvaiayarndaṉaieṉba; aḥdiyām

kūṟēm; vāḻiyar, endai! ceṟunar

kaḷiṟuḍaiaruñcamamtadaiyanūṟum

oḷiṟuvāḷtāṉaikkoṟṟacceḻiyaṉ

piṇḍanelliṉaḷḷūraṉṉaveṉ

oṇtoḍiñegiḻiṉumñegiḻga;

ceṉṟī, peruma!niṟṟagaikkunaryārō? (AḷḷūrNaṉmullaiyār, ANU. 46)

O man from the town, where

hating to stand in the mud,

a red-eyed buffalo tied to

a strong rope broke loose,

lifted a sharp thorn fence,

jumped into a pond with

stagnant water, caused fish

to dart away and vaḷḷai vines

with beautiful hollow stems

to get tangled,

and ate the watery lotus flowers

on which bees were swarming!

Who are you to us to quarrel?

They say that you brought someone

with dark, hanging hair like flowing

water into our house and married her.

We did not say that.

May you live, long my lord!

If my bangles that are bright like Allūr,

rich in paddy, owned by victorious king

Cheḻiyaṉ who won difficult battles against

enemies with elephants and crushed them

with his bright swords, slip, let them slip.

Lord! You can go where you want to go!

Who is there to stop you? (Tr. Vaidehi)4

One wife just wished to scorn implicitly the infidelity of her husband who had been unfaithful to her for some time. So she suggestively ‘hailed’ the country of her lord:

Oh lord of the fertile land! I am no body to sulk with you? You know, a robust buffalo of your country in the middle of the night left its shed clandestinely by snapping its rope. It removed the sharp thorny fence with its horns and went away from its shed. By daunting steps that scattered fishes hither and thither, they kept roaming in the watery field. Then, quietly it entered into a lotus tank located on the outskirts. There upon, it squeezed the vaḷḷai creepers. And blissfully it chewed lotus flowers that honey bees were flocking to. I did not but others say that you brought a young beautiful woman of long tresses to our home only to wed her. Long live my lord! Let my bangles be slip away from my arms in the way the resourceful Aḷḷūr of Pāṇḍiya Kingdom once got reduced to penury.

Thus, the wife described the clandestine character of the buffalo by which sarcastically she pointed out the infidelity of her husband who just returned from a brothel in the early morning. She discreetly made him to know that she was in fact aware of his infidelity, of his loose morals, of pleasing the harlot’s parents and relatives and of returning home at dawn for a formal stay. Here, the buffalo eventually stands for the hero, the fishes for the village people, the vaḷḷai creepers for her parents and the ‘lotus’ for the harlot.

In such descriptions, the speaker hesitates to express certain things openly but desires to dwell on each detail in a wordy caricature of a familiar incident in ‘Nature’ and through it more effectively conveys to the listener all the feelings and thoughts. More or less in a similar line to the above discussed poem, another heroine from marudam region points out the infidelity of her husband by using the same analogy. Again in this poem too, the buffalo with the same characteristics finds its place as the symbol/code to refer to the hero.

The hero, tired of his wife, has begun to visit a harlot who is more accomplished in terms of beauty. Forgetting his wife and child he roams around the place where the harlot lives. Consequent upon his improper attitude, his wife becomes very distressed. Finally, one day her husband does return to the home. However, the heroine not diminished her sulking over him. Thereby, the husband seeks the help of her tōḻi to pacify her anger. The tōḻi earnestly advises the heroine to forgive her husband in the interest of family life. Let us see how the following poem describes the clandestine attitude of the hero:

tuṟaimīṉvaḻaṅgumperunīrppoygai

arimalarāmbalmēyndaneṟimaruppu

īrntaṇerumaiccuvalpaḍumudupōttut

tūṅgucēṟṟuaḷḷaltuñcippoḻudupaḍap

painniṇavarāalkuṟaiyappeyartandu

kurūukkoḍippagaṉṟaicūḍimūdūrp

pōrcceṟimaḷḷariṟpugutarumūraṉ

tērtaravandateriyiḻainegiḻtōḷ

ūrkoḷkallāmagaḷirtarattarap

parattaimaitāṅgalōilaṉeṉavaṟidunī

pulattalollumō? maṉaikeḻumaḍandai

adupulanduuṟaidalvalliyōrē

ceyyōḷnīṅgaccilpadaṅgoḻittut

tāmaṭṭuuṇḍutamiyarāgit

tēmoḻippudalvartiraṅgumulaicuvaippa

vaiguṉarāgudalaṟindum

aṟiyāramma-ahduuḍalumōrē! (Ōrampōgiyār,ANU. 316)

In his town,

an old buffalo, his back wet and cool, his horns curved,

grazes on bright-flowered lilies

in a pond full of water and fish

sleeps all night in the oozing mud,

and then when dawn comes

walks out, crushing murrel fish with their fresh-smelling fat,

drapes himself with bright pakaṉṟai creepers,

and enters the ancient town like a warrior victorious in battle.

Tell me, woman of the house,

why are you angry with your man?

Why do you say,

“He brings women in his chariot, their ornaments exquisite,

their arms thin with desire for him,

so many the city cannot hold them all,

and they offer themselves to him again and again.

How can he bear living such a life?”

Surely a wife is foolish to show

such anger even though she knows

that woman strong enough to quarrel and live apart

must do without the goddess of prosperity,

must sift the stones from a small portion of rice,

cook it, and eat alone,

must suffer their sweet-voiced children

to suck their dried-up breasts. (Tr. George L. Hart, 1979: 129)

This is the marudam poem sketching aesthetically about a universal ever existing social problem of unfaithfulness of men towards their wives. It is delivered through the mouth of tōḻi who reasons to the heroine that she should forgive her unfaithful husband in the interests of herself and her child. We could paraphrase the arguments through which the tōḻi expresses her concern to the heroine in the following manner:

My dear friend, you know, in our Lord’s town, an old buffalo whose back is still wet and cool yet wishes to graze on newly blossomed lilies in a pond full of water and fish. It sleeps the entire night in the oozing mud without any hitch. Prior to the sun rise, it walks out of the pond crushing murrel fish of fresh-smelling fat. It enters our ancient town like a warrior victorious in battle by draping itself with dazzling pagaṉṟai creepers on its head. Tell me, why are you angry with your man? Why do you say: “He brings women accomplished in beauty and decked with ornaments in his chariot? Plenty of such women are living in our town who desire and voluntarily offer themselves to him. How can he bear living such a life?” It is not wise for a woman to quarrel even with her unfaithful husband who is the source of her prosperity, though she is strong enough to live apart without him. Otherwise, she would suffer alone in pathetic poverty where children even go without milk to suck from their mothers’ dried-up breasts.

Thus, the friend advises rather admonishes the heroine to forget and forgive her husband wholly for the sake of her family. We could say that the poem apparently advocates the worthy family life in which women are always propelled to adjust to their husbands (even to crooks, ruffians, criminals, psychologically disturbed men etc., simply they are their husbands) and compelled to sacrifice their individuality, liberty and inner space purely in the interest of their husbands and children.

The buffalo, signifying the unfaithful husband of the heroine, is compared to a fighting man, who returns covered with gore from battle and decked out with the garlands of victory. The comparison is ironic, for the buffalo is meant to be likened to the hero. “By saying that in his town, a buffalo grazes on lilies in the tank, sleeps in the mud, and then at dawn destroys murrel fish, drapes himself with pakaṉṟai, and enters the ancient town like a warrior, (the poet means) that the hero enjoys the harlots in that quarter (of town), spends the entire night in that base pleasure, and in the morning leaves, making his reputation small and causing much gossip” (Hart 1979: 130–31).

The bright-flowered lilies meant the beautiful and decorated young harlots. The buffalo oozing in the mud throughout night suggestively refers to the hero spending the whole night shamelessly in a harlot’s place. The buffalo draped in pagaṉṟai creepers on its neck meant to be likened to the remaining signs of the hero’s sleeping with the harlot in her colony. The crushed murrel fish of smelling fat became the image for the fresh young harlots who have failed to sleep with the hero until then.

Neydal – Seashore Region:

Neydal, the tiṇai representing seashore region, speculates on the anxious waiting of the heroine who is pondering in the afternoon hours before the sunset either in a premarital or post-marital love situation due to the non-arrival of her hero at the stipulated time. The region named after the flower “Water lily” (Nymphaeastellata) describes the pangs of separation of the lovers in the background of seashore.

Mīṉ (sea fish), ciral (kingfisher), cuṟā (shark), iṟāl (shrimp), aṉṟil (an unidentified seashore bird perhaps the legendary ‘lovebirds’), kurugu (heron), nārai (crane), aṉṉam (swan), alavaṉ (crab), āmai (tortoise), mudalai (crocodile) etc., are the birds and beasts of the neydal tract which is filled with sandy soil and the flowers such as āmbal (White lily – Nymphaea lotus alba), kuvaḷai (Blue Nelumbo – Pontederiamonochoriavaginalis), creepers/plants such as tāḻai (Screwpine – Pandanusodoritissimus), climber, kaidai(Fragrant screwpine, Pandanusodoratissimus), ñāḻal (Orange cupcalyxedbrasiletto), and trees such as puṉṉai (Mast-wood, Calophylluminophyllum) etc.

Sangam poets portrayed skilfully the pangs of separation of neydal heroines in numerous poems. The neydal heroine feels utterly sad either over the failed or delayed return of her lover (in clandestine love) or husband (in post-marital life) who left her and went on to an alien country to become either educated or to prosper in conducting some business or to take part in war defending his land. On his separation, the heroine becomes so anguished/tormented due to social stigma and of course to loneliness. Her sufferings and pangs have no bounds after the sunset, especially at midnight. Here in the following neydal poem (Naṟṟiṇai (NṞI) 303), the heroine shares her anguish, anxiety and agony with her tōḻi, the friend.

Oliyavinduaḍaṅgiyāmamnaḷḷeṉa

kalikeḻupākkamtuyilmaḍindaṉṟē!

toṉṟuṟaikaḍavuḷcērndaparārai

maṉṟappeṇṇaivāṅgumaḍaṟkuḍambait

tuṇaipuṇaraṉṟiluyavukkuralkēṭṭoṟum

tuñcākkaṇṇaḷtuyaraḍaccāay

namvayiṉvarundumnaṉṉudaleṉbadu

uṇḍukolvāḻi tōḻi! teṇkaḍal

vaṉkaipparadavariṭṭaceṅkōl

koḍumuḍiavvalaipariyappōkki

kaḍumuraṇeṟicuṟāvaḻaṅgum

neḍunīrccērppaṉtaṉneñcattāṉē! (Madurai ĀrulaviyanāṭṭuĀlampēriCāttaṉār, NṞI.303)

It is midnight.

Its noise stilled,

the boisterous town is quiet in sleep.

Again and again I hear

the yearning cry of the pair of aṉṟil birds

from their nest in the crooked spathe

of the huge-trunked palmyra in the courtyard,

a place long haunted by a god,

and my eyes do not close in sleep

and I seem to grow thin from the pain I feel.

Does he know his lovely-faced woman suffers

because of him, friend,

he from a village by the deep-water ocean,

where a killer shark roams, filled with hate

after tearing his way through a net

of curved knots and straight sticks

thrown by the strong-handed fishermen in the clear sea?

(Tr. George L. Hart, 1979: 93)

The poem so vividly portrays the compelling charm of the neydal region in which the heroine suffers from her loneliness. From behind the conventional symbolization of anxious waiting, there emerges a picture of the stillness of seashore region where at midnight the yearning cry of the pair of aṉṟil birds (unidentified seashore birds perhaps the legendary ‘the lovebirds’) adds fuel to her loneliness. Here, the single aṉṟil bird of the pair signifies the heroine who is suffering most from separation from her lover. The roaming shark which tears the nets of fishermen can be taken as a symbolic outlet of the heartless gossiping nature of village people, who ridicule her severely despite her being well-protected by her parents.

The foremost mood of the neydal tiṇai is deeper, and more pathetic than any other tiṇai: a woman has given herself to a man, and unless he marries her she is ruined. In many neydal poems, the lover has abandoned his beloved, leaving her alone to suffer in distress. Often, she is distraught because of gossip about her affair with a man who does not seem to care for her. See how a heroine here expresses her grief to her friend.

ilaṅguvaḷaiñegiḻaccāayyāṉē

uḷeṉēvāḻi tōḻi cāral

taḻaiyaṇialgulmagaḷiruḷḷum

viḻavumēmbaṭṭaveṉnalaṉēpaḻaviṟaṟ

paṟaivalantappiyapaidalnārai

tiraitōyvāṅkuciṉaiyirukkum

taṇṇantuṟaivaṉoḍukaṇmāṟiṉṟē. (Ammuvaṉār, KṞT. 125)

May you live long, my friend!

My festival-like virtue

that excelled that of women

wearing on their loins

clothing made from

the trees on the slopes,

has gone away with the lord

of the shores,

where an old white stork

who has lost his wing strength

sits on a bent tree branch

that is soaking in the waves.

I am wasting away; my bright bangles

have slipped; and I am still alive. (Tr. Vaidehi)5

The heroine had given her noble virtue gracefully to a man from coast by having an intimate affair with him. After sometime, the man parted from her to alien country, seeking a better livelihood. He has not returned to her for quite some time. Thereby, the heroine became depressed and disillusioned. She lost her charming youth and became weak too. Even the bangles have slipped away from her arms. But still she is alive since she is hopeful of her man’s returning back. Here, the heroine describes her pathetic condition by employing an analogy wherein she suggestively refers to herself to an old white stork which has lost its capacity to fly up any more to anywhere, but still sits on a bent tree branch that is soaking slowly in the ocean waves.

In the image ‘the stork’ symbolizes the heroine and its ‘white colour’ signifies ‘her noble virtue’ or ‘chastity’. The uḷḷuṟaiuvamam is that like the stork which has lost its feathers and is unable to fly, the heroine has lost her virtue and strength and is struggling to live. The bent tree branch refers to the heroine’s hometown which is not sympathetic to her condition. The waves of the ocean are the gossip of people, as suggestively implied here in the poem. The stork is hopeful that the waves will become still one day. So does the heroine hope that her man will return to her one day. That is why she is still alive.

Pālai – Desert Region/Wasteland Tract:

Pālai, the tiṇai representing a desert region or parched wasteland area, speculates on separation which occurs when love is subject to external pressures that drive the lovers apart in the noon of the scorching summer, either in premarital or post-marital love situation. The region is named after the plant “Blue-dyeing rosebay” or the tree “Wrightia” (Wrightiatinctoria). The pālai or wasteland is not seen as being a naturally occurring ecological condition. It emerges when the adjoining areas of mountain and forest land tracts wither under the heat of the burning sun. Thus, it could be seen as a mixture of mullai and kuṟiñci landscapes, rather than as a mere sandy area. This landscape is associated with the theme of separation, which occurs when love is subject to external pressures that drive the lovers apart.

Palli (lizard), ōdi (chameleon/garden big lizard), ōndi (chameleon/garden big lizard), puṟā (pigeon), kaḻugu (eagle), ceṉṉāy (red fox), yāṉai (elephant), puli (tiger) etc., are the birds and beasts of the pālai region which is filled with sand and stones.

In pālai, man seems to be fighting against nature in its most unfertile manifestation. The hero usually undertakes the journey alone either to educate himself, or at the military assignment from his kingdom to wage wars with enemies, or to earn wealth in the interest of his family members’ well-being. When the parents and brothers of the heroine are not in favour of their relationship, then both the hero and the heroine ‘run away together’ (uḍaṉpōkku, i.e. ‘elopement’) to an alien place and travel through the bone-dry wilderness that is filled with thieves and other hazards. The dangerous journeys undertaken by the hero individually as well as with his beloved through desert areas are vividly described in pālai poems. The obstacles and dangers either faced by himself or with his ladylove are also realistically portrayed. Let us see here how a heroine expresses her worry over the journey of her beloved in fearsome wild landscape:

ceṉṟunīḍuṉarallaravarvayiṉ

iṉaidalāṉāy”eṉṟiciṉiguḷai

ambutoḍaiamaidikāṇmārvambalar

kalaṉilarāyiṉumkoṉṟupuḷḷūṭṭum

kallāiḷaiyarkalittakavalaik

kaṇanariiṉaṉoḍukuḻīiniṇaṉarundum

neyttōrāḍiyamallalmociviral

attaeruvaiccēvalcērnda

araicēryāttaveṇtiraḷviṉaiviṟal

eḻāattiṇitōḷcōḻarperumagaṉ

viḷaṅgupugaḻniṟuttaiḷamperuñceṉṉi

kuḍikkaḍaṉāgaliṉkuṟaiviṉaimuḍimār

cempuṟaḻpuricaippāḻinūṟi

vambavaḍugarpaintalaicavaṭṭik

koṉṟayāṉaikkōṭṭiṉtōṉṟum

añcuvarumarabiṉveñcuramiṟandōr

nōyilarpeyardalaṟiyiṉ

āḻalamaṉṉōtōḻiyeṉkaṇṇē. (IḍaiyaṉCēndaṅkoṟṟaṉār, ANU. 375)

“He will not stay away for long,

and yet you do not stop worrying,”

you say, friend.

In the hot, frightening wilderness he has entered,

wild young warriors whose shouts echo on forking paths

test their arrow shots,

killing travelers, even though they have no money,

and feed them to the birds.

There, while foxes move around them,

vultures eat fat,

their strong, close-set claws bloody

as they sit on a large-trunked yā tree,

on a branch as thick as the trunk of the elephant

that killed the northern newcomers,

crushing their soft heads,

when Iḷamperuñceṉṉi, the Chola king,

whose thick arms always gain victory in battle,

sure in his shining fame,

crushed the fortress of Pāḻi with its coppery walls

to finish the work of his line.

Even though I know he will return safely,

my eyes, friend, refuse to stop crying. (Tr. George L. Hart, 1979: 134)

Thus, the heroine is seriously worried over the safety and well-being of her beloved who had already set foot in the wildest landscape in search of wealth. Here in the poem, wild young warriors (presumably thieves), vultures, foxes, wild elephants have been depicted as the life-endangering elements in order to portray the wild nature of the desert region, where men in ancient days went on either to educate themselves, or on a military assignment for their kingdoms to wage wars with enemies, or to earn wealth in the interest of their family members’ well-being as stated earlier. Except in a few poems, there was no description of the women accompanying their respective beloveds in such wild regions for the reasons mentioned above. The heroine eloped with her lover and travelled to alien places only to lead a family life against the will of her parents and brothers. Most of the pālai poems quite naturally have depicted wild nature with the same life risking elements described in the above poem.

Contrary to the typical pattern of pālai poems, some heroes, either before or in the middle of their journey, leaving their lovers in suffering, used to remember their sweethearts and worry over their safety and well-being. For instance, a hero who is yet to travel in the narrow paths on the cliffs decides not to proceed to alien country while leaving his ladylove suffering. He sincerely worries that his ladylove would be in serious danger from some unknown quarter when he leaves her alone for a longer period. See how the hero is expressing himself to his lonely heart over his concern for his ladylove.

vaṅgākkaḍandaceṅkaṟpēdai

eḻāaluṟavīḻndeṉakkaṇavaṟkāṇādu

kuḻalicaikkuralkuṟumpalaagavum

kuṉṟukeḻuciṟuneṟiariya yeṉṉādu

maṟapparuṅkādalioḻiya

iṟappaleṉbadīṇḍuiḷamaikkumuḍivē (Tūṅgalōriyār, KṞT. 151)

Leaving her,

and not considering that the

journey is difficult through

the narrow paths on the cliffs,

where a male vanga bird has left

his red-legged female, and a hawk

dives down and attacks her,

and unable to see her mate,

she cries out in a few short

plaintive notes,

sounding like music from a flute,

might be the end of my youth. (Tr. Vaidehi)6

The hero, though departed from his beloved for quite some time, does not wish to keep away from her forever. He sincerely loves her and is seriously concerned for her well-being. So concerned with the safety and security of his ladylove is he, and foreseeing the awaiting danger to her, that the hero cancelled his journey before setting off even at the cost of putting his prosperous life at risk. Though the journey is a necessary one, he abandoned just before proceeding to a foreign country, as he judged living with his ladylove was more important than everything else.

The uḷḷuṟai here is that the hero thinks that the heroine might have to suffer like the red-legged female bird, if he leaves her and goes to earn wealth. The vaṅgā bird mentioned in the poem could be a small variety of stork. The term eḻāl refers to a hawk which is notorious for attacking its prey. Symbolically, the former stands for the hero whereas the latter stands for any troublemaker/wrongdoer/ miscreant.

Tiṇai Mayakkam – Overlapping of Tiṇais (The Aspects of Love):

Some poems in Sangam literature may speak about one particular aspect of love theme but at the same time they refer to other aspects of love too. This cluster of love themes in a poem is possible and is placed under the category known as ‘tiṇai mayakkam’7 (overlapping of tiṇais). For example, let us consider a very famous kuṟiñci-tiṇai poem to understand how certain elements of flora and fauna serve as symbols in a given situation.

yārumillaittāṉēkaḷvaṉ

tāṉadupoyppiṉyāṉevaṉceygō?

tiṉaittāḷaṉṉaciṟupacuṅkāla

oḻugunīrāralpārkkum

kurugumuṇḍutāṉmaṇandañāṉṟē. (Kabilar, KṞT. 25)

Only the thief was there, no one else.

And if he should lie, what can I do?

There was only

a thin-legged heron

standing on legs yellow as millet stems

and looking

for lampreys

in the running water

when he took me. (Tr. A.K. Ramanujan, 1985: 17)

The word “thief” applied to the lover, and the millet-stem legs of the heron are looking for fish in the water while they are secretly making love. Here in the poem, the predatory nature of the heron is what is in focus. The bird looking for fish in the running waters is like the lover taking his woman. The heron, indifferent and selfish, is contrasted with the heroine, who gives herself to her lover (Hart 1979: 9).

From another point of view, the unseeing, uncaring heron is meant to be likened to the world. This type of an individual heron who is not attending to anything but his own prey, and the lack of witnesses are part of the suggestion implied by the text. While the heroine gives herself to her lover, the world is concerned only with finding something to eat in order to stay alive. The world’s only concern with the heroine’s love is to gossip about it. The heron is also meant to be likened to the hero, who shares the selfish attitude of the world. The heron’s eating eels from the running water is a symbol for sexual gratification: like the heron, the hero is concerned with gratifying himself, not with love and its responsibilities. And the woman remembers the heron vividly because it crystallizes her fears regard-ing her lover’s possible treachery.

While correlating the imagery of the poem with the theory of fertility, George L. Hart observes (1979: 9):

In the sexual act with her lover and as the object of gossip afterwards, the heroine is as helpless as a wriggling eel in the beak of the heron. The bird’s legs are like millet stems. The millet stem holds grain, the source of life for others and the fruit of fertility, while the heron’s legs hold a bird that is predatory, that uses others but contributes nothing to their welfare. While it seems that the hero’s act might lead to marriage with its fruit (children), it is fact only a predatory act, and the hero has no intention of marrying his new mistress.

Though the poem is firmly set in kuṟiñci (lovers’ union, the millet stems), the water and the heron seem subtly to suggest neydal (anxious waiting), and the mood is close to marudam (infidelity) or fear of it. Thus, the vivid moment of love-making (with which the poem climaxes) and the focussed image of the predatory heron, representing that moment, that stays in the woman’s mind, contain past experience, present doubts, and future fears: three different landscapes are suggested. According to A.K. Ramanujan (1985: 284), “The poem is thus a mosaic of given forms, and a dance of meanings as well.”

To sum up, we could say that the plants, birds and beasts depicted in Sangam love poems in one way or another symbolize something beyond their concrete meaning appearing explicitly in the poems. Sangam love poems mostly symbolize or describe the heroes with robust, mighty and forceful beings such as the honey bees, hawks, buffalos, male pigeons, stallions, male elephants, tigers, lions etc., However, heroines were referred to by way of soft and gentle flowers or plants like lotus, water-lily, jasmine, Strobilantheskunthiana, birds like parrot, pigeon; or animals like cow, doe, she-elephant etc. It may be stated here that the classical Tamil poets, more often than not, also perceived the female gender as a soft or weaker section living under the shadow of and care of their mighty counterparts.

Note:

This article was published earlier in the International research journal “PANDANUS’ 13/2, NATURE IN LITERATURE, ART, MYTH AND RITUAL”, Vol. 7, No. 2, Philosophical Faculty, Institute of South and Central Asia, Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic, 2013, pp. 07–31.

Footnotes / References:

- Birds and beasts, that includes insects (ant, honey bee, fly etc.), amphibians (frog, toad etc.), crustaceans (shrimp, crabs etc.), reptiles (lizard, snake, crocodile, tortoise, turtle, etc.), mammals (cow, buffalo, pig, bear, elephant etc.), birds (parrot, peacock, hen, fowl, heron, eagle etc.) and animals (lion, tiger, elephant, wild dog, fox etc.)

- In Tamil, the terms maññai (purely a literary usage) and mayil (mostly a colloquial usage) both commonly refer to peahen and peacock. It is the adjectives “āṇ” (male) and “peṇ” (female) added to the above terms that actually make the difference.

- Vaidehi, Kurunthokai 101–200 (Sangam Poems Translated by Vaidehi), Accessed on 05th June 2014. <http://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.wordpress.com/kurunthokai-101-200/>

- Vaidehi, Akananuru1–50 (Sangam Poems Translated by Vaidehi), Accessed on 05th June 2014. <http://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.wordpress.com/akananuru-1-50/>

- Vaidehi, Kurunthokai 101–200 (Sangam Poems Translated by Vaidehi), Accessed on 05th June 2014. <http://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.wordpress.com/kurunthokai-101-200/>

- Vaidehi, Kurunthokai 101–200 (Sangam Poems Translated by Vaidehi), Accessed on 05th June 2014. <http://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.wordpress.com/kurunthokai-101-200/>

- The term ‘tiṇai mayakkam’ literally means “the confusion or blending of regions”.

About the Author

Govindaswamy Rajagopal, as a serious scholar of Tamil literature has written numerous books/research article that give valuable insights into Tamil literature, both popular and classical, by applying sociological and psychological theories. He works as a Professor at Delhi University.

More about him at: http://www.du.ac.in/du/uploads/Faculty%20Profiles/2015/Modern%20Indian%20Language/Oct2015_MILS_Rajagopal.pdf